Post Like It’s 2009: Year-In-Review Reviewed

Should I post this? This question alone occupies a good amount of collective cognitive load throughout the day, whether we are strategically held back Likes from Instagram like thirsty dogs or when friends ask us if they should do option 1 or option 2. The latest excuse to post is the feel-good, introspective (humble-bragging) Year-In- Review stories, where we excavated all of these checklist accomplishments of

- Can you still have a good year if the world is in shambles?

Year-in-reviews (YiR) used to be a way for periodical publications to cover events of the past year through the lens of their domain. Now, through the massive amount of individuals’ data available, shackled by corporations, we can be served a remix of our digital footprint with an overly animated bow on top that tells us what musician’s astrology sign we align with the most.

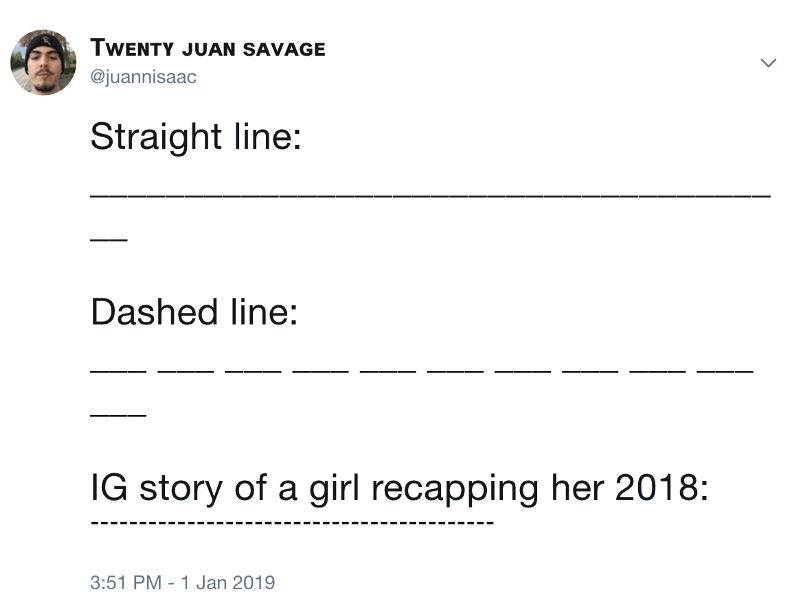

2018 heralded the mainstream adoption of the YiR IG Story recap. This curation falls into the same trappings of doing more unpaid online labor. Although reminiscing on your past year feels like an organic activity, it is an intentional byproduct: Instagram did away with transitory snaps in favor of maintaining an Archive, which in turn gives them the ability to track how we look back at our past selves. This behavioral data – what internally motivates us to choose one 2018 moment over another – is more dangerous than facial recognition or knowing what we choose to follow or like.

A note to myself: In 2019, I hope you structure your life to create as many bullet point accomplishments, milestones, and travel plans so that you can have more aspirational data for Instagram to mine.

But 2018 wasn’t enough for us. We needed to go farther back – back 10 years, to 2009. Remember when Facebook’s wall-to-wall was the original social 1:1? There were no DMs or Messenger or WeChat. There was a self-awareness of relevance that wasn’t quite as aware or relevant as we understand those terms today. It was pre-Instagram and people actually liked Facebook.

One of the reasons we revel in this particular year has to do with how Instagram had yet to disrupt the format. On Facebook at the time, you could create albums of your landscape or portrait photos, imitable of a pre-Internet collection. That year, I created an album called “squares”, a theme inspired by the 120 format. Little did I know that Instagram would force users to adopt this 1:1 ratio as a way to distinguish their service: a disguised cognitive shortcut that compressed and jammed expressions of our personality into square pegs so that it is all the more easier for machines to eat it up. The format, standard, and infrastructure is the message.

However, the implication of having a square photo goes beyond also using this ratio to fill up portrait orientated screens or having users feel that they are “creators” by editing for the correct focal point. It allowed IG this new ownership of photography through this ironing into a single homogeneous format and then a market for influencers who knew how to capitalize on the new standards. It is profound how much our notion of photography, the self, and celebrity has been mutated in the last 10 years because of this minor but wide-reaching decision of ratio.

Although we were freed from those constraints in 2015, these values remain, done again with 9:16 Stories. By cramming our 2009 photos into a square or story format, we bring those past selves into the present, retrograding and extinguishing any of that Internet optimism we used to hold. We have formalized #tbt in a viral template that collectively puts this particular digital era to rest: RIP 2009 -2019. Out of the 5.5 billion people on earth, 5 billion have a phone, and 4 billion have smartphones. We’re reaching peak saturation of having analytics on almost everyone while A.I. is being embedded in anything it can be embedded in. It’s the end of the beginning. An anonymous egg becoming the most liked photo has become the harbinger of a new digital age – a metaphor of potential shaped by the past that could easily collapse.

The fastest backlash that people have against this #10YearChallenge was that we were giving facial cognition algorithms a leg-up with data on how we age. But these corporations already had that data: I joined Facebook 15 years ago with some tagged photos that are dated even before that. There is enough stored about our complexion and bodies, enough to reconstruct and manipulate our forms like voodoo dolls: our faces power the machine learning processes that allow for #twinning and fake people be birthed from server farms. How we think and understand, how we swipe or click, however, constantly evolves and so do the mechanisms to interrogate our very being.

We want to be given reasons to post, but one that especially pleases omniscient algorithm. Our gods are the algos, platforms (e.g. FAANG) are our religion, and brands are the clergy. When we talk about the reach of Facebook, with the amount of users climbing up to 2 billion, it is only second to Christianity. The new clergy of brands create holidays or co-opt previous ones in order for brands to reach us and get us to re-post their message: there are almost 3 hashtag holidays a week. Who manufactures these holidays? Today is National Nothing Day. There will be a rom-com for #NationalTequilaDay with an ensemble cast. These freshly minted holidays represent the cementing of non-organic virality.

Even though our perception of time seems to be manipulated by the endless and uneven firehose of news and social, a year remains the same amount of time. Will we be celebrating 2010 in 2020? Time will tell, but this kind of nostalgia peaked this month.